Breaking the Cycle: Don’t Let Shame and “Old” Rules Govern You

By Laura Elizabeth DeHority, LMFT

This past week, I had the privilege of watching a young person graduate from Army boot camp. In the process of becoming a soldier, she learned to trust her instincts and to quiet down any internal voices of fear that could endanger her in conflict. As her mentor, a parent and as a therapist, I had to smile. So many of us, especially we parents of kids who have experienced trauma, could use this very kind of training.

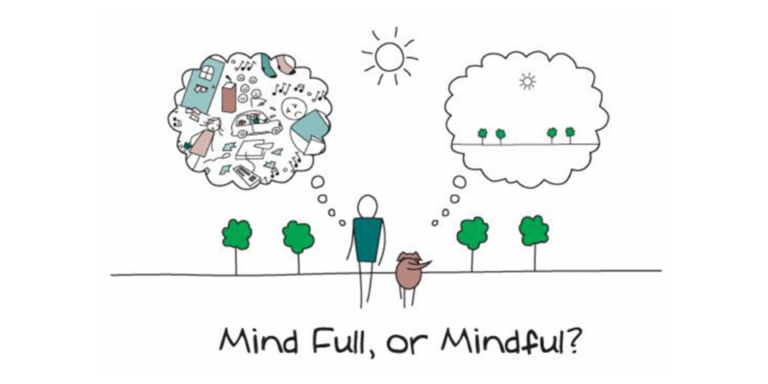

Generally during conflict, there are two conversations happening simultaneously. The first one is happening externally. This external conflict often involves comments directed toward us that may be judgmental, unfair, inaccurate or hurtful. These painful words are internalized and set off a dialogue in our head as we recall our own past experiences. Our inner critic almost always narrates this secondary, internal conversation. The external conflict is like a gas can; and if you have a burning internal conversation happening, there is likely going to be an explosion. To put out the fire, we as parents need to be aware of our internal voices.

Do you ever hear your mother or father in your voice as you are having a conversation (or conflict) with your kids? Is the voice you hear one of shame or empathy—and what does that even mean?

Brené Brown, a psychologist who studies the role of shame in relationships defines shame as “the intensely painful feeling or experience of believing that we are flawed and therefore unworthy of love and belonging – something we’ve experienced, done or failed to do makes us unworthy of connection.” Another way of putting it is — feelings of shame are false feelings stemming from our family of origin.

Shame is often felt surrounding the following topics:

- Appearance and body image

- Money and work

- Motherhood/Fatherhood

- Family

- Parenting

- Physical/mental health and addiction

- Sex

- Aging

- Religion

- Speaking out

- Surviving trauma

- Stereotyping and labeling

(Source: Brené Brown, Connections Curriculum, 2009)

How we speak to others and ourselves is tied to our childhood home. The ideal is to have healthy dialogue even around difficult subjects, which builds space for empathy. Unfortunately, in some homes, shame or fear was used to keep children’s behavior inline. We must choose the words that we say to ourselves and the stories from our critic that we listen to, potentially acknowledging our own empathetic shortcomings. When we sense that a conversation with our child is going toward external conflict, it is important that we calm the internal critic so that we are most available to use the great conflict management tools that we have in our toolbox.

How these complex topics are discussed can either lead parents directly into or away from conflict. But know this: superficial conflicts are nearly always cover for unspoken fears about choices that have a lasting impact. If you can determine what is fearful within you, you can more likely defuse the conflict and be available to come alongside your child in what fear they are going through. When you are safe with your own thoughts, you have the direction to take a helpful path and with time, will be increasingly less likely to fall into the pattern of reverberating negativity or shame around any of the above topics. You will hone the skills to not take on their hurts and fears as part of your past history.

Whether we like it or not, the thoughts of our internal critic are shaped by our family of origin’s rules or the rules of our extended communities (church, peers, etc.). Common phrases – or unhealthy rules – can hold power over us well into adulthood. The intention is often to avoid conflict, but using this type of judgment simply replaces the external conflict with more layers of internal shame.

Phrases are listed below with the underlining messages recipients often hear:

- “Don’t get mad.” (Don’t express yourself.)

- “If you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all.” (You’re not nice.)

- “Always look good to the rest of the world.” (You’re never good enough.)

- Just be happy. Don’t make waves. (You don’t matter.)

- If you can’t do it right, don’t do it at all. (You’re going to fail.)

These rules, which are maladaptive tools that are often used to avoid conflict within the adolescent home inadvertently, cause people to rebel, shut down, feel extremely mad inside, and experience panic or self-doubt. These rules can also manifest themselves into physical ailments such as headaches and/or stomach aches. Again, these statements that you may have heard in the past served the purpose of shutting down the conflict externally while they grew shame internally. This has left you with two battles: internal vs external or past vs. present.

Since you are reading this, I can guess that you have received lots of helpful positive strategies to have more successful conversations. Do you find yourself giving up on those strategies? Has that inner critic voice inside your head kept you from trying something you wanted to try even if “impractical?” Have they silenced you when you wanted to speak up?

If you find yourself governed by the inner critic who is just full of unhealthy rules, which were imprinted in your youth, be aware of how those can be exploited. People in your life may take advantage of your resistance to express yourself or the alike. Do not let these unhealthy rules serve as power tools for those who undermine your personhood. While these rules may have helped you when you were younger, they most likely need to be modified or eliminated for your mature life. Undoubtedly, your child has been exposed to deeply painful conflict in the past. The most powerful first step for you to help them is to take the best possible care you can of your own internal dialogue about past fear.

When you read both lists of hot topics and unhealthy phrases, how do you feel? You may find that at least some of them trigger a feeling inside of you. The question is, which feeling? Is it shame? Fear? Anger? Resentment? Regret? Sadness? Less than?

When you admit these things to yourself with compassion, the inner critic loses its power and the control in your head is given back to all of the powerful tools that you have learned. Remember that gas can and matches early in the post? When we quiet our inner critic, there is still a match. It might become a torch as your child realizes that they cannot manipulate you. But instead of a gas can, you have changed how you show up. Now your internal story might be flame retardant fuzzy pajamas covered with hearts.

All of this sounds great. But it can’t be that simple. The answer is that the solution is simple, but it requires a lot of ongoing practice to overcome all of that history.

So how can you use empathy for yourself and your children instead?

Confront those negative feelings with empathy and alternative thoughts, such as:

- I am enough.

- I need some help here, and help is available.

- This is big, and I need to make many small steps to move toward resolution.

Specific examples of self-care and self-compassion statements include the following:

- “I need to be warm and understanding toward myself when I suffer, fail or feel inadequate instead of ignoring the pain or punishing myself.”

- “I need to recognize that I am my own best advocate, and my best empathy for others is knowing what is happening within myself.”

- “I need to recognize hard stuff is hard and take the best possible care to confront my feelings without going back to old rules. I need to not expect others to do the work within me when I am failing to do my own work.”

Incorporating these strategies is straightforward but it will not be easy and will require a commitment. Releasing yourself from unhealthy rules or shame you may have learned from your family of origin begins with awareness. Granting empathy to yourself is a start to becoming a more empathetic parent. When you quiet your inner critic with kindness, your child will begin to experience the change in you. You will experience the change in you. There will still be conflict and difficulty, but you will have new tools to avoid the two-way explosion